Alright y’all, it’s time to talk about seed starting. I’ve officially taken the first concrete step toward the 2021 garden – I started cold stratifying my rosemary seeds yesterday. Next steps: I’ll read a seed packet and transfer its info to my seed starting spreadsheet, and repeat, until I’ve laid out all the info I need to get started when seed starting time comes. Which I’m eagerly counting down to. So today, we’re talking about how to read a seed packet!

(Sidebar: I’m running an experiment this year – I’ll be cold stratifying a variety of herb seeds and testing those against ones I just plant normally. Stay tuned for the results. We’ll also be running lots of experiments on indoor starts vs. direct sowing).

If you’ve found your way here, you’re likely a new gardener, or at least new to growing from seed.

We’ll be breaking down the ins and outs of how to read a seed packet: what the various fine print means and how to make it useful to you. This post is long, but it’s chock-a-block full of useful info!

If combing through fine print makes you stir crazy just thinking about it, bear with me. As a bonus, I’m sharing a free worksheet to help you move from disconnected details to concrete seed starting plan. And if you’re the type of learner who needs to see a demonstration rather than read a bunch of words, feel free to scroll past the lexicon to “Anatomy of a Seed Packet,” where I actually break one down!

Seed Packet Lexicon

Theoretically, a seed packet should give you the basic info you need on how to grow the plant. Unfortunately for the beginner gardener, there’s no industry standard format for what that info is. It could be some mix of any of the terms below plus more. Now, that’s not to say there isn’t plenty of useful information on any given seed packet, some may just be more useful than others. A packet should at the very least tell you when and how deep the seed should be planted, how to space the plants and how long it should take the fruit to be harvestable.

I’ve included photos in this post of seed packets from five different seed companies to give you an idea of the variety of info and presentation style.

Annuals:

Plants that perform their entire lifecycle, from seed to bloom/fruit to seed within a single growing season.

Biennials:

Plants which require two years to complete their life cycle.

Perennials:

Plants which persist for many growing seasons. Generally, the above-soil portion of the plant dies back with the cold weather and then regrows in the Spring from the same root system.

Note: annual, biennial and perennial are most likely to be listed for flower varieties.

Open-pollinated:

Seeds produced via natural pollination (i.e. bees), without help from humans. These seeds will be true to type. So if you save seeds from a plant that grew from an open-pollinated seed, those seeds will produce the same plants year after year.

Heirloom:

Heirloom seeds are open-pollinated seeds that have been saved and passed down across many years – sometimes hundreds of years! All heirloom seeds are open-pollinated, though not all open-pollinated seeds are heirloom.

Germination:

The process by which the seeds begin to grow into the plant. On a seed packet, companies will list a number of days (i.e. 7-14 days) that they estimate a seed will take to germinate under ideal conditions.

Propagation:

The process of producing a new plant from a parent plant.

Ideal conditions (germination):

Some seed packets may lay out the seed’s ideal germination conditions explicitly. For example, rosemary, which has notoriously spotty germination, prefers both light and warmth (70-80°F) to germinate. If a packet doesn’t say, it’s fair to assume the seed will need warmth and moisture to germinate and strong full-spectrum light once it does so the plant can begin photosynthesizing.

Ideal conditions (plant growth):

A packet may list a plant’s preferences for sun vs shade, whether it’s frost-tender or frost-hardy, or what sort of soil fertility, moisture level, pH, etc.

Direct sow:

Indicates a seed that will do best if it’s planted straight into the garden, rather than started indoors. Often this will be a seed for a plant where we consume the root (carrots, radishes), a legume or a curcurbit (cucumbers, squashes). Some varieties – like curcurbits – will say you can direct sow or start early. Unless your season is super short, direct sowing is likely best. But again, I’m testing that wisdom this year.

Start indoors/start early:

Indicates a seed that will thrive best if it’s started indoors and then planted out after some number of weeks. This may be because it needs a longer growing season or is a heat lover (like tomatoes, peppers and eggplants), or even because transplants can often better withstand pest pressure. The seed packet will recommend how early to start the seed indoors as a number of weeks prior to your last frost date.

Depth:

This will likely be an absurdly small number like ¼-inch. The rule of thumb is to plant a seed twice as deep as it is large. For tiny seeds like carrots, that may mean just sprinkling the seeds on top of the soil and then sprinkling a bit more soil on top to cover. Don’t worry about planting too shallowly – newbie gardeners are much more likely to plant too deeply. If you’re wondering why none of your seeds aren’t coming up, that could be why. Basically, a seed only contains so much energy to get the plant going. If you plant too deeply, the seed may run out of energy before the seedling can break the surface of the soil, and then it will die without light.

Plant/row spacing:

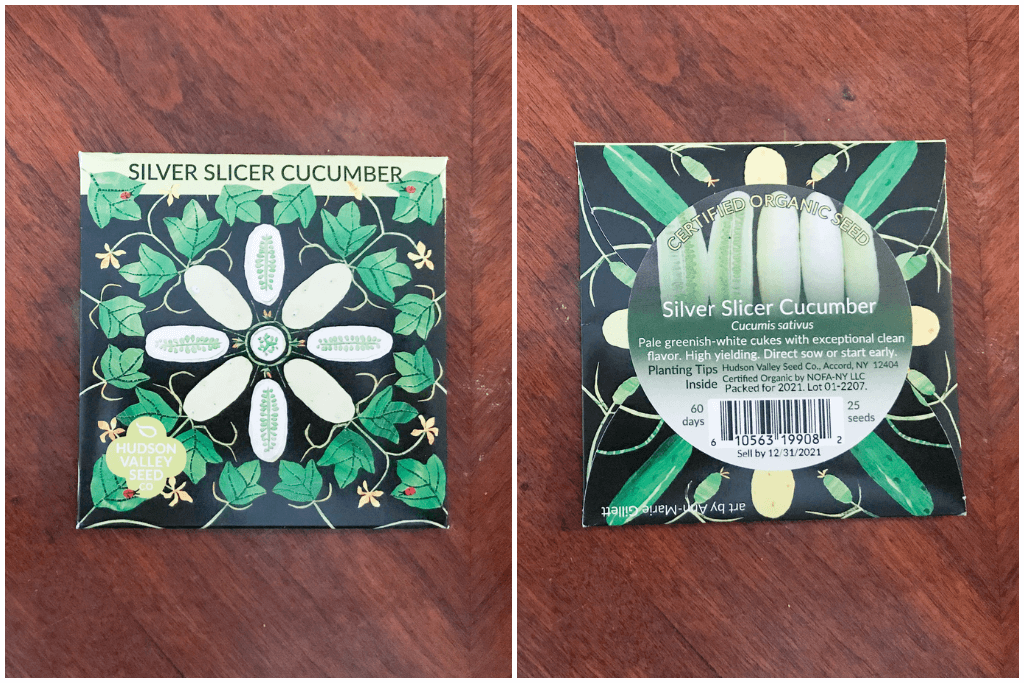

How far apart plants should be planted. This can be as little as a couple inches for radishes to a couple of feet for tomatoes. For direct sown plants, you’ll likely sow more thickly and then thin to the appropriate spacing once plants have germinated. Note that most seed packets assume planting in rows. If you’re planting in a raised bed, just give the plant that much space all around. You can play with spacing if you’re employing vertical gardening methods. On the silver slicer cucumber packet above, it suggests spacing 5 feet between rows because it’s a vining plant. I don’t have that much space, but I will be training my cukes up a trellis so I can get away with decreasing the spacing.

Support:

Some seed packets may indicate if the plant will need support like a cage, stake or trellis. Many don’t, however. So if you don’t know how a plant grows, do a quick google. Definitely plan to provide some sort of support for indeterminate tomatoes, cucumbers, and other vining plants like peas or pole/runner beans.

Days to maturity:

How long it will take a plant to produce ripe fruit when growing under ideal conditions. For example, a small radish will take 25-30 days to be ready to harvest under ideal conditions. Because it’s a frost-hardy crop, that doesn’t mean I can’t grow that radish under less-than-ideal conditions, it just means it might take longer to grow to harvestable size.

Note that when a seed packet states days to maturity, it’s usually referring to the number of days from transplanting date to ripe fruit, not seed sowing date. Unless of course the packet is for a seed that should be direct sown.

The biggest thing you need to know when interpreting what a seed packet says about days to maturity is how long your growing season is. You can’t grow something that takes longer to mature than your season is long (unless you deploy season extenders like a polytunnel). If you’re unsure how long your season is, you can calculate it yourself by counting the days between your last and first frost date. Or you can utilize the power of the internet: Input your zip code and the Farmer’s Almanac will tell you your frost dates and season length! For example, here in zone 6a, my last expected frost date is April 30, my first expected frost date is October 10, so my season is – on average – 162 days.

Frost-tender or frost-hardy/tolerant:

Indicates whether a plant variety can survive a light frost. For example, most brassicas and roots are frost-hardy, meaning they will survive. Whereas other plants like tomatoes are extremely frost-tender, meaning they’ll die if they frost. Note that even frost “hardy” plants are usually only hardy down to a hard frost, or 28°F.

Indeterminate or determinate:

Determinate plants top out at a specific size and often produce a bumper crop over a short period. Indeterminate plants will keep growing to fill the space and time they have, producing over a longer period of time. You need to know whether your varieties are indeterminate or determinate to provide them proper support and spacing.

Anatomy of a Seed Packet:

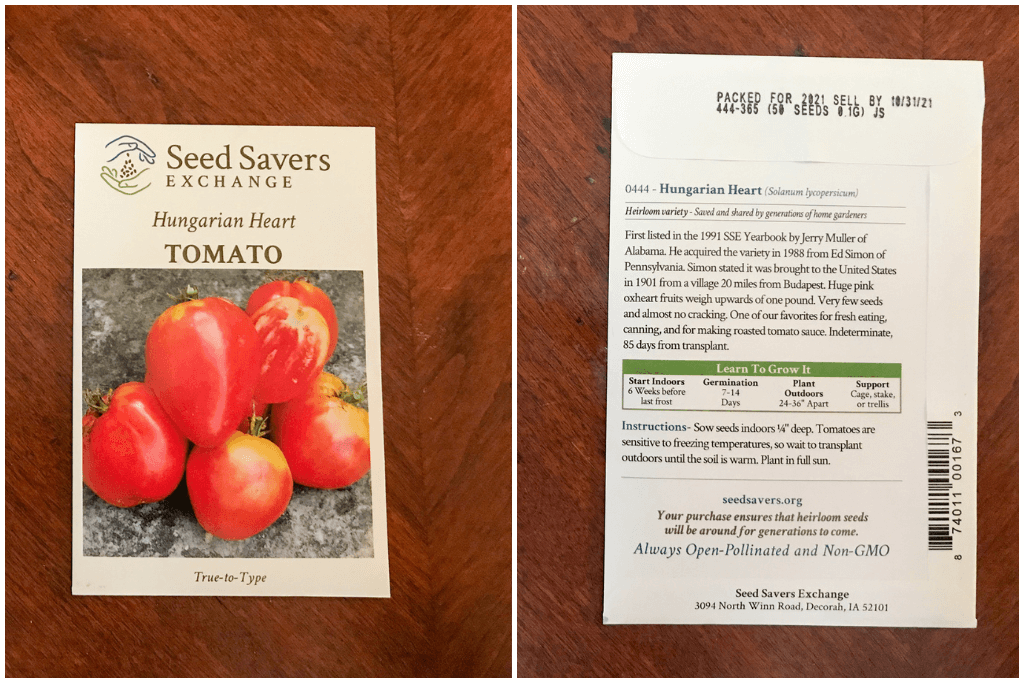

Alright, now that we have the lexicon down, let’s actually break down this Hungarian Heart Tomato seed packet from Seed Savers Exchange. Any info on the packet that I haven’t covered in the lexicon above should be pretty self-explanatory.

So starting on the left-hand side of the image, with the front of the seed packet:

We first have the name of the seed company, Seed Savers Exchange.

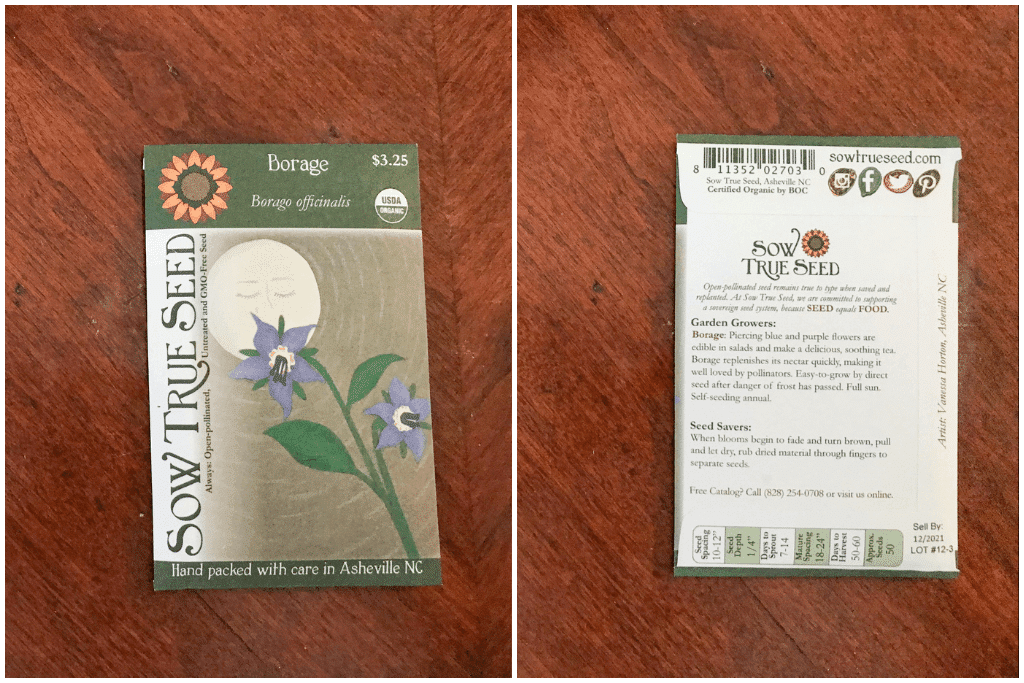

Next, the packet lists the name of the variety – Hungarian Heart Tomato – along with an photo of the variety. Note, some packets may have an artistic illustration rather than a photo, such as in the silver slicer cucumber or borage packets above.

And the final thing on the front of this envelope, they state this tomato is “True-to-Type.” This indicates the variety is either an heirloom or a stable hybrid (in this case it’s the former). It means I can save the seeds from this tomato and reliably grow another Hungarian Heart tomato.

Now for the back, where the good stuff is:

On the flap, you’ll see it reads, “Packed for 2021. Sell by 10/31/21. 444-365 (50 seeds 0.1g) JS.”

The 444-365 and JS aren’t useful to us – it’s manufacturer’s info for the warehouse. “Packed for 2021” and “Sell by 10/31/21” tell us these seeds were produced last year and packed for this growing season. And come November, Seed Savers Exchange will begin selling seeds for 2022.

Seed companies are required by law to list the year the seeds were packed for. That doesn’t mean the seeds are only good for 2021! As long as you’re storing your seeds well, they should germinate for many seasons (with the exception of alliums like onions and garlic).

In fact, a few years ago some Russian climbers stumbled upon 32,000-year old seeds buried by an Ice Age squirrel in Siberia that still germinated and grew out a fertile flower!

The older the seeds the more spotty its germination may be. So if you know you’re working with seeds that are a few years old, just toss an extra or two into the cell, or start an extra cell, in case the first doesn’t germinate.

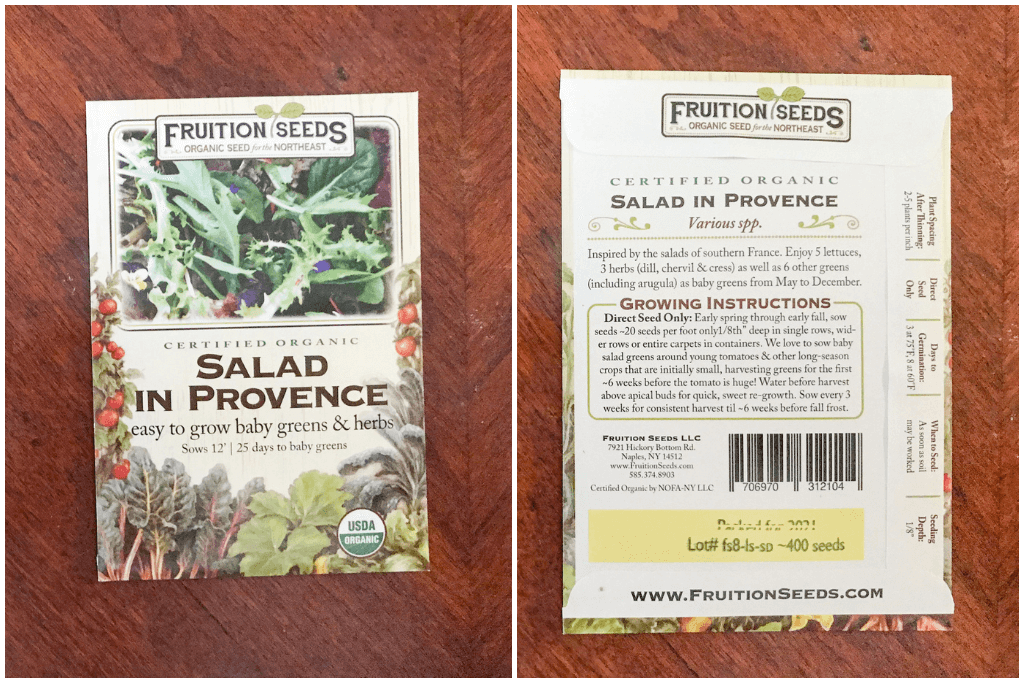

Then you’ll see in parentheses, the flap tells us the size of the packet – “50 seeds” and “0.1G.” This is pretty basic: this packet is guaranteed to have at least 50 seeds, and it weighs .1 grams. How big a seed packet is varies from seed variety to seed variety and seed company to seed company. Some, like Fruition Seeds and Hudson Valley Seed Co., offer different sizes of seed envelopes. So if you’re growing on a large scale, you can get 500 beet seeds instead of 100, for example.

If you’re a home gardener, it’s likely one envelope per variety will be plenty to get your through the year. I ordered a second packet of French Breakfast Radish seeds this year, thinking I’d be low from last year. And then it came and I realized each packet has 500 seeds and I’d planted maybe 50 last year. Oops. I think the smallest seed packets I have still have 25 seeds. More commonly they have 40-100 seeds.

Below the flap, we get to the info that’s more important for growing:

“0444- Hungarian Heart (Solanum lycopersicum)” – a.k.a. The English and scientific names of the variety and its number in Seed Savers Exchange’s catalog.

Next the envelope tells us it’s an heirloom variety, as well as what heirloom variety means – that it was saved and shared by generations of home gardeners.

As in this seed packet, many heirloom seed packets will have a brief description of the variety and its history. At the end of this description, we learn this tomato is indeterminate and that it takes 85 days from transplant to produce ripe fruit. I plan on trellising all of my tomatoes, so I’m good as far as it being an indeterminate variety. And now I know I can expect a ripe tomato in late July/early August based on my last frost date.

The “Learn To Grow It” box shares the critical information as far as how to read this seed packet:

Here, I learned that I need to start this tomato seed 6 weeks before my last frost. Tomatoes should usually be started 6-8 weeks early, so that’s normal. It also says this variety takes 7-14 days to germinate – crucial info for when after two days I get impatient and convinced my seeds will never sprout so I should plant more.

Anyone else ever feel that gardening is a perpetual lesson in patience?

Alright, it says to plant outdoors 24-36 inches apart. Cool. My plan is 24 inches, and I’ll prune to one or two leading stems to ensure good airflow. We’ll talk more about that when the time comes, but basically tomatoes are prone to blight with too much moisture so good air flow is crucial.

Finally for this section, Seed Savers Exchange tells me this tomato variety needs support in the form of a cage, stake or trellis. Again, I’ve got that covered.

Now for the last crucial bit: the Instructions

“Sow indoors ¼” deep. Tomatoes are sensitive to freezing temperatures, so wait to transplant outdoors until the soil is warm. Plant in full sun.”

A quarter-inch is not deep at all. If you’re not overly neurotic about details (or at least are trying to be less so, *ahem* me), just remember the rule of thumb I shared above – plant twice as deep as the seed is wide.

Tomatoes are tropical plants. They will die if it freezes. More, they’ll just get stunted if it drops colder than their liking. In general, you want to wait until your lows are in the mid-50s Fahrenheit to plant them out. So even though my last frost date is at the end of April, really mid-May is my safe planting date. This year, though, I have hoops and row covers, so I may try to push the boundaries a little.

And of course, as tropical, heat-loving plants, tomatoes love sun. When I was container gardening in an apartment, I tried to get away with partial shade, because it’s all I had. Save yourself the heartbreak and tiny, tiny yields. Give the tomatoes what they want: sun and lots of it.

To finish this seed packet off, we have a bit more info about Seed Savers Exchange.

They share their website, that your purchase helps ensure the preservation of heirloom varieties (because they’re a nonprofit seed bank) and that their seeds are always open-pollinated and non-GMO. Still confused about what that means? Check out my post on sourcing heirloom and organic seeds. Finally, at the very bottom, their mailing address. And on the side, a bar code for warehouse processing purposes.

Now, remember – all this info pertains to commercially-produced seed packets.

But loads of us get seeds from swaps and friends/family. You may just get a little plastic baggy or paper envelope with nothing more than the name of the variety on it.

In that case, Google is your friend! You can always find more info about that variety on the internet. You’ll also find, the more you learn, the more there are predictable patterns. For example, most tomatoes are started indoors 6-8 weeks before your last frost date. If you want a fun challenge, grow your gifted seeds out following the basic game plan for whatever type of plant it is and be surprised by the specifics along the way!

And that, my friends, is how you read a seed packet!

If you’re still feeling a little overwhelmed, feel free to download this worksheet to help you translate seed packet to planting instructions! If you’re an analog type person, these can be printed and then sorted by how many weeks early the seeds should be started. Then you can just work through them in order, week by week!

And I’ll be back next week with a breakdown of how to develop a seed starting plan!

Pin it for later:

Leave a Reply